Optimization of Digital Objects

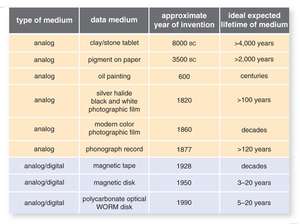

As the ArtoP archive begins to grow, and the team begin to process our collection for preservation and dissemination we are becoming increasingly aware about the need to consider the so called decay of the digital object. Whilst it is commonplace to think of preservation of physical objects, the digital tends to come with associations of atemporality and durability. In fact, as new digital formats are regularly being developed as a UCLA research team identified in 2013 'digital images must be migrated about every year and a half, lest they become inaccessible'. Furthermore if one considers that 35mm film can last for decades, and pigment on paper whose longevity can extend into thousands of years (Boyda, 2013) then digital images have a much shorter life than their physical equivalent. The 'decay of digital objects over time' is not typically scrutinsed especially in the arts and when dealing with born digital content, file formats and digital decay is an important consideration.

As Bollacker suggests digital media have a fragility that goes beyond the digital data itself but extends to the software required to access this data in the future. Using systems such as archivematica and ATOM allow one to mitigate for this, ensuring that storage and preservation extends beyond the digital object itself to the software. The difficulty when talking about visual representations as a digital image (still or moving), is that the physicality of the image moves from the real to the virtual which presents wider sets of ontological questions regarding the nature of the digital image. As Binkley (1990) put it the paradox of some that at once can be seen, but also consisting of a number as 'an invisible abstraction', bits and bytes. In the digital space, the connection between physical materiality and image information is not so clear cut. Whereas a painting does not rely on any intermediary to 'translate' or render visible the image, digital images require both hardware and software to make it visible.

Our archive will for the most part be processing a large number of digital images (still and moving), some of these images will be photographs of a real drawing, painting, poster, cartoon, filmed performances. Other times, the digital images or videos we collect will be 'born-digital', that is to say created on the computer without ever existing in a physical space. Consider, for example. the rendering of a computer generated animation whereby animators will produce a final movie file that will be either a sequence of digital still images or a digital moving image file format that can be played on a player as a piece of software on a computer or mobile phone.

However before rendering the images, the animator would have produced a vast amount of so-called digital assets, from 3D digital sculptures of characters and environments, digital paintings as backplates or as textures to be projected onto these sculptures, virtual lighting rigs, to motion data that will used to drive the characters' movement. The collection of these various digital items within specialist 3D computer animation software are able to come together to produce the final computed images that we view as the film. One of the challenges of the ArtoP project, when engaging with digital artists in Nigeria, was to engage in discussions with artists to donate, not only the final rendered film, but also the different components and digital files that make up the film. These assets become important to the discourse of artmaking practice within digital environments because they are able to 'paint a picture' that describes both the tools that artists are using and the methods they adopt.

The Preservation Of Complex Objects Symposia (POCOS) and the International Network for the conservation of contemporary art (INCCA) are two knowledge sources that offer more information about the preservation of these types of digital objects. As we have established artists' digital work can consist of material that is in flux and relational, and currently as Barok (2019) claims existing digital archiving is somewhat rigid in its approach to the preservation of complex digital objects. These are challenges that the team is facing as it considers how to best optimize a digital object for archival purpose. What format do the files get stored as? How are they rendered visible for dissemination and distribution? Furthermore what metadata should be prepared for these objects? And what relational heirarchies do we need to consider when grouping these objects into series and collections?

C.(2019) 'Archiving complex digital artworks', Journal of the Institute of Conservation, Vol 42, No 2, pp 94-113.

Binkley, T. (1990), 'Digital Dilemmas', Leonardo. Supplemental Issue, Vol. 3, Digital Image, Digital Cinema: SIGGRAPH '90 Art Show Catalog (1990), pp. 13-19

Bollacker, K. (2010), 'Avoiding a Digital Dark Age', American Scientist, March Issue, Vol. 98, No. 2, p. 106. https://www.americanscientist.org/article/avoiding-a-digital-dark-age Accessed 12/01/2020.

Boyda, J. (ed.), 'Preserving the Immaterial: Digital Decay and the Archive', Spectator 33:2 (Fall 2013), pp. 6-10.

Papageorgiou P. (2015) 'Toward a Conceptual Emulation Framework for the Preservation of Archaeological 3D Visualizations', New Review of Information Networking, 20:1-2, pp. 214-218.